Is this the most obscure allusion or reference to Nick Drake ever?

With 2020 established as such a tragic year for so many people, you may not have noticed the recent sad news of the passing of Millie Small, the Jamaican singer commonly known as Millie, and famous for the 1960s international smash hit record ‘My Boy Lollipop’. If you’ve read any biographies of Nick Drake, or viewed recent obituaries of Millie, you will probably be aware of the connection between Millie and Nick, namely Millie’s recording of ‘Mayfair’ in 1970, a song which Nick never ‘officially’ recorded or released himself. What I would like to do is take you back to the era this association between Nick and Millie was made, by highlighting an obscure reference to the song in a contemporaneous publication, before looking into the value and meaning of ‘Mayfair’ within the context of the careers of both Millie and Nick.

Record Song Book, later known as Words, was a popular magazine in Britain during the 1960s and 1970s. Non-glossy, and in presentation more like a cheap comic than a magazine or newspaper, it specialised in lyrics from current pop songs. From personal memory, I recall that Record Song Book was bought mainly by kids and younger teenagers, who would use it, often enough, to sing along to their favourite chart hits. I have a particular recollection from school of one classmate buying the magazine and singing Don Mclean’s ‘Vincent’ repeatedly. It seemed incongruous at the time as the lad in question was known as a hard-nut!

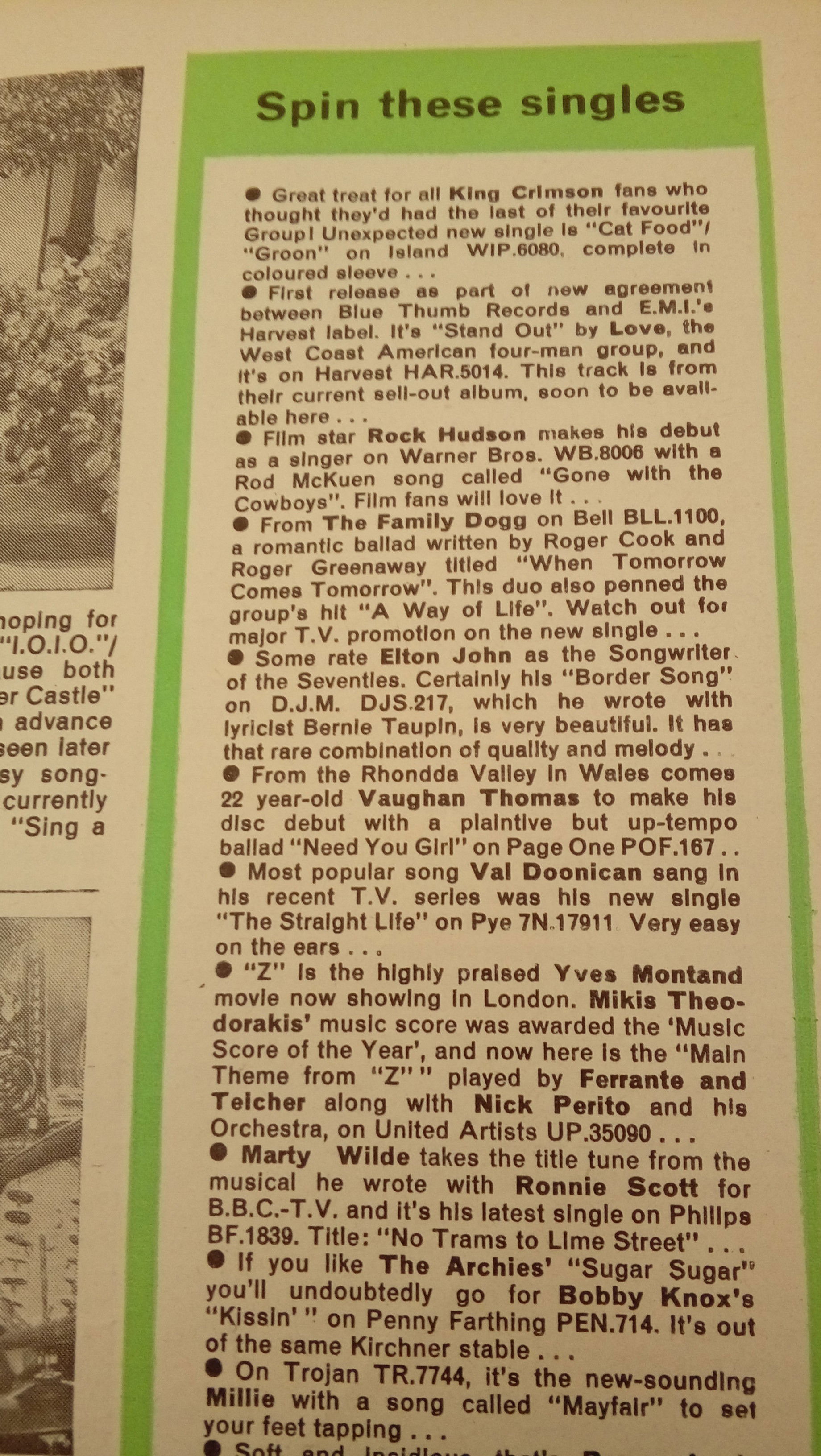

As well as lyrics, the magazine included articles on celebrities, not always strictly from the pop world, and roundups of the latest vinyl releases, whether albums or singles.

The edition highlighted in this article was issued in May 1970, and featured the then up and coming actor, Edward Woodward. In the singles roundup, known as ‘Spin these singles’, you will notice ‘Mayfair’ by Millie. It was a reggae version of the song, and released on the Trojan record label, which, again as you may well know, not only specialised in reggae but was closely linked to Island Records, Nick’s label.

The track was included in Millie’s album Time Will Tell, released, like the single, in 1970. Laurence Cane-Honeysett, writing for Record Collector in his article ‘Millie Small The Lollipop Girl’, tells us that both the album and single formed part of Millie’s campaign to re-launch her career, but in a new direction, one which would be reggae orientated, and without the homely persona which had characterised her previous stance. With regard to the latter aim, the very same Record Song Book describes Millie in the ‘gossip’ section as bouncing back ‘with a new sophisticated more sexy image’. The backing band for this fresh enterprise was no less than The Pyramids, also known as Symarip, famous within reggae circles for the classic track, ‘Skinhead Moonstomp’.

Trevor Dann in his biography of Nick Drake, Darker Than The Deepest Sea, tells us that Millie’s recording of Mayfair was also part of an effort by Nick’s manager and publisher, Joe Boyd, to promote Nick as a songwriter, and that the track was arranged and produced by none other than Nick’s musical collaborator, Robert Kirby. Patrick Humphries in Nick Drake: The Biography, quotes Boyd as stating that Millie probably heard the song through Chris Blackwell, the head of Island Records. Humphries also tells us, quoting Robert Kirby, that Nick was pleased with the cover, and we are informed again that Kirby produced and arranged the album. I need to state nonetheless that other sources credit the production of the album to Eddie Wolfram. The label on the single of Millie’s Mayfair does the same.

For some Nick Drake fans, it may come as a surprise that as early as 1970 one of his songs was recorded by an international pop star, backed by a top-notch reggae outfit. Unfortunately, despite the pedigree of the participants, Millie’s ‘Mayfair’ was not a commercial success, and on face value, leaving aside any marketing deficiencies that might or might not have occurred, there are obvious reasons for this.

On first listening to the track you are inclined to think there is a mismatch between song and genre. The lyrics of ‘Mayfair’ seem just too ethereal, or esoteric, to suit what was clearly meant to be a danceable pop song, one ‘to set your feet tapping’ as stated in Record Song Book. Successful reggae tracks at the time often, although not always, carried social messages or statements. We have ‘Love Of The Common People’ by Nicky Thomas, Greyhound’s ‘Black And White’, Horace Faith’s ‘Black Pearl’, and Bob and Marcia’s cover of the Weldon Irvine and Nina Simone song, ‘Young, Gifted and Black’. In fact, all the aforementioned records are covers, and all are full of exuberance. In comparison, Millie’s ‘Mayfair’ comes across as rather quirky, despite Nathan Wiseman-Trowse, in Nick Drake: Dreaming England, referring to it as a would-be ‘re-imagining’ of the English experience along ethnic lines.

Yet a mismatch between the song and genre was not, perhaps, the main problem. Laurence Cane-Honeysett may well describe the single as an able interpretation of the song, but in itself the song was possibly not good enough to secure Millie a hit record, and particularly when compared with the quality of the songs covered by Millie’s reggae and Trojan label contemporaries. The quality issue is backed up by Chris Healey in his piece, ‘If Songs Were Lines In A Conversation…’, an analysis of early Nick Drake songs included in the anthology Remembered For A While. Healy describes ‘Mayfair’ as the kind of song you expect from songwriters on their initial steps towards acquiring their skills, and he goes on to state that it is odd that it became Nick’s first song to be covered commercially. Of course, since when was a good song a required necessity for a hit single? You may well ask the question but would need to understand that Robert Kirby’s arrangements added little value to the single, and on repeated listening the track becomes monotonous and dull.

To add insult to injury, and returning to the ‘mismatch’ theory, Laurence Cane-Honeysett informs us that the B-side, the overtly political ‘Enoch Power’, did more to grab the attention of reggae aficionados than ‘Mayfair’. Penned by Millie and Eddie Wolfram, the song was a protest against the anti-immigration British politician Enoch Powell, who became infamous for his ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, and its message therefore aligned closely with the experiences of Britain’s Afro-Caribbean community, and anyone else for that matter who followed reggae. Banned on the radio, ‘Enoch Power’ was not able to save the single sales-wise.

Despite any doubts we may harbour about the worth of ‘Mayfair’ as a song, I still believe it is an important indicator of how Nick Drake saw and portrayed the world around him, especially through its lyrics, although I’m not sure, for some at least, that such a realisation is readily forthcoming. Pete Paphides, in ‘Come To The Garden’, another item from the anthology, compares ‘Mayfair’ to the social satire of the songwriter Jake Thackray, and quotes Robert Kirby describing it as a song that mocks Mayfair’s rich. Trevor Dann compares it to The Kinks’ ‘Waterloo Sunset’ and The Beatles’ ‘Penny Lane’, detecting within it the influence of Nick’s mother, Molly. If we wanted to go further, I could propose that the song is a take on Donovan’s ‘Sunny South Kensington’, given that Dann believes, with good reason, that Nick was heavily influenced by Donovan and that Nick, as Dann also tells us, had a copy of Donovan’s Mellow Yellow which included the track. I have to point out nevertheless that the album was not released in the UK, although of course Nick’s copy, apparently given to him by his friend Simon Crocker, could have been acquired elsewhere. To add to the vagueness, parts of Mellow Yellow were included in the UK release of Sunshine Superman (the album that Brian Wells, in the anthology piece ‘You Look To Find A Friend’, states that he and Nick played to death), but not ‘Sunny South Kensington’.

In reality, ‘Mayfair’ is not social satire, and neither is it a charming ditty. The song is a portrait of a social scenescape viewed through the eyes of someone who is both aware of nature and prone to suspecting that things aren’t always what they seem on the surface, especially with regard to people. In its lyrical content we find an early grasp of what Ian MacDonald described as nature codes. In his seminal article, ‘Exiled From Heaven’, as seen in The People’s Music, MacDonald mentions that throughout much of Nick Drake’s work there are codes and symbols relating to natural occurrences and objects. In ‘Mayfair’ we have such codes in abundance, Sun, rain, Moon, light, dark, morning, afternoon, and night. On the notion of suspicion, there is a perception of circumstances being strange, a word repeated throughout the song and which almost caused it to be called ‘Mayfair Strange’, and we learn of people taking on supernatural forms, particularly when we hear of faces interred with mystical powers.

You’re forgiven should you believe that this essay is an exercise in how to squeeze as much mileage out of an obscure reference as possible, a reference consisting of a few lines from a largely forgotten magazine from the 1970s. My only defence is that when writing about Nick Drake, nothing is ever straight forward. There’s always so much to say.